Opera is an art form in which singers and musicians perform a work combining both text and musical score in a theatrical setting. Opera incorporates many of the elements of spoken theatre, such as acting, scenery, and costumes, and may include dance. Performances are given in an opera house, accompanied by an orchestra or musical ensemble.

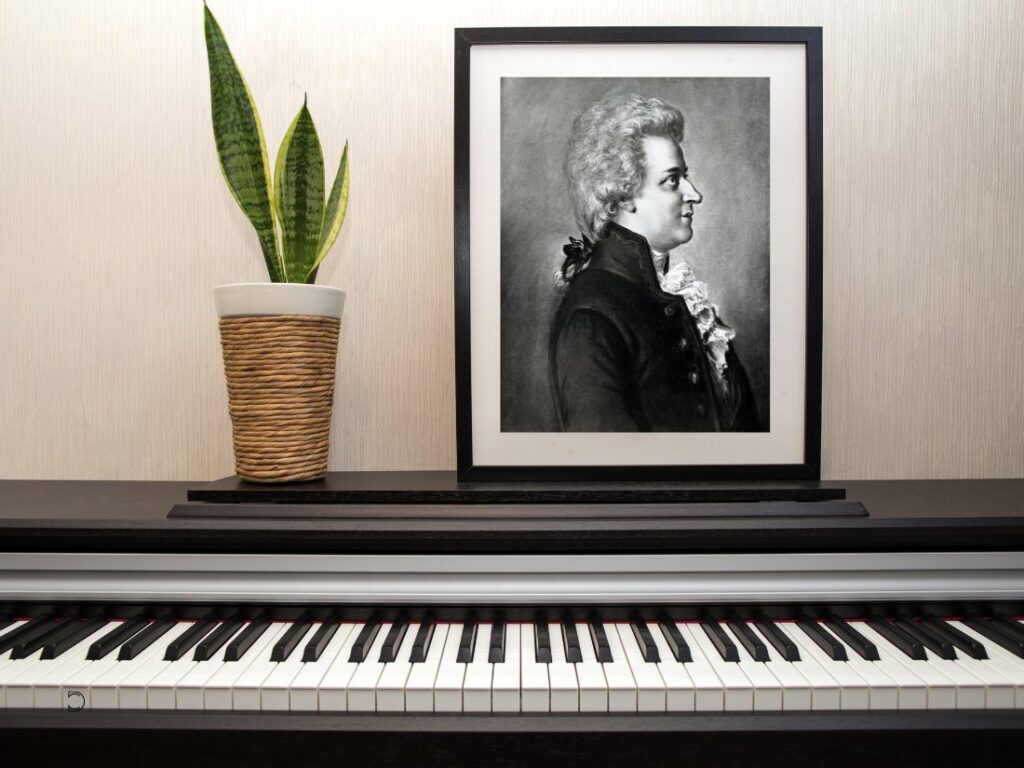

Opera is part of the Western classical music tradition. It started in Italy at the end of the 16th century and soon spread throughout Europe: operas in the 1760s. Today the most renowned figure of late 18th century opera is Mozart, who began with the opera “Seria” but is most famous for his Italian comic operas like The Magic Flute, Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and Cosi fan tutte. The first third of the 19th century saw the high point of the bel canto style, showcasing works created by Rossini, Bellini, and others that are still performed today.

It also saw the advent of the Grand Opera with works of Auber and Meyerbeer, while the late 19th century has been labeled the “golden age” of opera, led and dominated by Wagner and Verdi. The popularity of opera continued throughout Italy and contemporary France to Puccini and Strauss in the early 20th century. Thanks in part to the rise of recording technology, singers such as Enrico Caruso became known to audiences beyond the circle of opera fans. Operas were also performed on (and written for) radio and television.

The words of an opera are known as the libretto (“little book”). Some composers, such as Richard Wagner, have written their own libretti, while others have worked in close collaboration with their librettists, e.g., Mozart and Da Ponte.

Traditional opera consists of two modes of singing: recitative, plot-driving passages sung in a style designed to imitate and emphasize the inflections of speech and aria in which the characters express their emotions in a more structured melodic style. Duets, trios, and other ensembles often occur, and choruses are used to comment on the action.

The word opera means “work,” which suggests that it combines the arts of solo and choral singing, declamation, acting, and dancing in a staged spectacle. Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long. In 1637, the idea of a “season” (Carnival) of publicly attended operas supported by ticket sales emerged in Venice.

Before such elements were forced out of opera seria, libretti had featured a separately unfolding comic plot as sort of an “opera-within-an-opera.”

One reason for this was an attempt to attract members of the growing merchant class, newly wealthy but still less cultured than the nobility, to the public opera houses. These separate plots were almost immediately resurrected in a separately developing tradition that partly derived from the commedia dell’arte, a long-flourishing improvisatory stage tradition of Italy.

Just as intermedia had once been performed in between the acts of stage plays, operas in the new comic genre of “intermezzo”, developed largely in Naples in the 1710s and ’20s, were initially staged during the intermissions of opera seria. They became so popular, however, that they were soon being offered as separate productions.

Opera seria was elevated in tone and highly stylized in form, usually consisting of secco recitative interspersed with long arias. These afforded great opportunities for virtuosic singing, and during the golden age of opera seria, the singer really became the star.

A common trend throughout the 20th century, in both opera and general orchestral repertoire, is the use of smaller orchestras as a cost-cutting measure; the grand Romantic-era orchestras with huge string sections, multiple harps, extra horns, and exotic percussion instruments were no longer feasible.

As government and private patronage of the arts decreased throughout the 20th century, new works were often commissioned and performed with smaller budgets, very often resulting in chamber-sized works and short, one-act operas. Another feature of late 20th-century opera is the emergence of contemporary historical operas, in contrast to the tradition of basing operas on more distant history, the re-telling of contemporary fictional stories or plays, or on myth or legend.

The Metropolitan Opera in the United States reports that the average age of its audience is now 60. Many opera companies have experienced a similar trend, and opera company websites are replete with attempts to attract a younger audience. This is part of a larger trend of greying audiences for classical music since the last decades of the 20th century.

Smaller companies in the US have a more fragile existence, and they usually depend on a “patchwork quilt” of support from state and local governments, local businesses, and fundraisers. Nevertheless, some smaller companies have found ways of drawing new audiences.

In addition to radio and television broadcasts of opera performances, which have had some success in gaining new audiences, broadcasts of live performances in HD to movie theatres have shown the potential to reach new audiences. Since 2006, the Met has broadcast live performances to several hundred movie screens all over the world. A subtle type of sound electronic reinforcement called acoustic enhancement is used in some modern concert halls and theaters where operas are performed.

Although none of the major opera houses “…use traditional, Broadway-style sound reinforcement, in which most if not all singers are equipped with radio microphones mixed to a series of unsightly loudspeakers scattered throughout the theatre“, many use a sound reinforcement system for acoustic enhancement.

I recently discovered a great operatic tenor from Italy, Giovanni Cavaliere. His talent is unmatched, along the lines of Andrea Bocelli, Luciano Pavarotti, and Placido Domingo, among others.

I dare say it has something different from these big names, her voice, her powerful and at the same time penetrating voice that shakes the walls of the rooms where I have heard and shook even the abs and some people cry during the audio zone in which I was invited. I was playing a few opera pieces, Verdi’s Otello and Puccini’s Turandot. We heard him sing the Neapolitan song, O Sole Mio. I have never felt so much power and beauty of tone altogether. At the same time, his theater acting involves a whirlwind of emotions, which is difficult to escape, even for those who have never witnessed the live singing of a tenor.

I saw with my own eyes, including myself, acute people out of the hearing with tears in his eyes and a heart full of satisfaction. He is equally comfortable in the execution of works of Puccini, Verdi, and religious forms in music (Ave Maria) for his unique musical style. While in Italy, he already has a following and a history of theatrical debuts as the IDA; we eagerly await his return to the United States (where he sang at the United Nations in 1998).

What strikes Giovanni Cavaliere is their youth and seamless physical fitness. We have always been accustomed to seeing the Tenors of history rather than in the flesh, also for the physiological need of the acoustic resonance of the case body. Well, This Tenor combines a perfect physique for a powerful voice and harmony. Some experts call it a perfect “Verdi tenor”; his voice, powerful and heroic, allows him to play Othello, as a few others.